The largest drug distributor in the US has been accused by the Teamsters union of a pivotal role in the country’s opioid epidemic.

The union is urging shareholders to force a public reckoning this week, a move prompted by one member’s heartrending account of the death of his son.

The Teamsters, which has 1.4 million members in the the US, is using its substantial fund holdings in McKesson, the fifth-largest corporation in the US, to press for leadership changes.

This comes after the company paid the largest financial settlement of its kind amid lawsuits accusing it of “flooding” the country with prescription painkillers.

The union is asking shareholders to impose an independent chair to run the board and come clean on the company’s role in the epidemic after McKesson paid $150m to settle justice department accusations that it failed to report suspicious deliveries of vast numbers of opioid pills at the heart of the epidemic.

The crisis has claimed more than 300,000 lives over the past 15 years.

The Teamsters also want shareholders of McKesson meeting in Dallas on Wednesday to vote against a huge bonus for the present chairman and CEO, John Hammergren, one of the highest paid executives in the country.

Ken Hall, the union’s general secretary-treasurer, has called McKesson’s role in the opioid epidemic “one of the most tragic failures of corporate integrity – a devastating breakdown in values, culture, ethical conduct and regard for the law”.

McKesson has consistently denied any wrongdoing but in May it agreed to a Teamster demand to set up an independent committee to review the company’s actions in the $9bn a year prescription opioid business.

The Teamsters’ move throws a spotlight on the distributors whose role in the epidemic has been less widely known than that of drug manufacturers, prescribing doctors and pharmacists. McKesson is the largest of the “big three” drug distributors who were revealed by the Charleston Gazette-Mail to have delivered 423m opioid pills over five years to West Virginia alone, a state of 1.8 million people with the country’s highest rate of drug overdose deaths.

The distributors have also been accused by a former senior Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) official responsible for overseeing prescription drugs of using political pressure to avoid accountability and of “lacking a conscience”. The companies have defended their role as doing no more than delivering legal drugs to licensed pharmacies to fill prescriptions written by doctors. They say that opioids account for only a small fraction of their business.

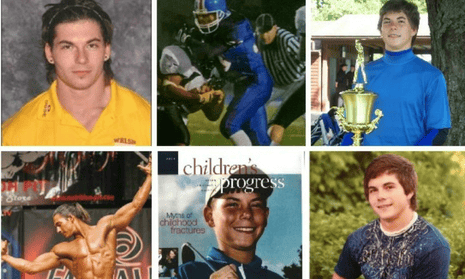

The Teamsters action follows a heartrending appeal by one of its members to the union’s annual convention last year. Travis Bornstein spoke about the death of his 23-year-old son, Tyler, who became hooked on opioids prescribed after an operation for a sports injury. After repeated attempts at rehab he started using heroin and overdosed. His body was found in a parking lot after he was left there by another user.

Bornstein, a former US Marine, gave a passionate speech in which he wrangled with his guilt for failing to recognise that Tyler’s addiction was a disease and not a moral failing.

“I learned I have to forgive a whole lot of people for me to recover and move forward. Guys like the drug dealer, the person who dumped my son’s body in a vacant lot like a piece of trash, the doctor who prescribed opiates to a kid, but most of all myself. I was embarrassed and ashamed to talk to anyone about my son’s addiction. I thought I failed as a father and that my son was a moral failure. I was embarrassed of my son,” he told the conference.

Bornstein, who is president of his union local in Ohio, appealed for donations to an organisation he founded, Breaking Barriers, to help others addicted to opioids. After he spoke, the conference’s schedule was delayed while a stream of other members recounted the toll of opioids on their families.

“Teamsters from all across the country started coming to the mic and making pledges to support Breaking Barriers and then in doing that they started telling their stories too: ‘Hey, I lost my nephew.’ ‘I lost my mom and my dad,’” said Bornstein. “That don’t happen if the epidemic isn’t real. If everybody isn’t feeling it and going through it. That was all spontaneous. I poured my heart and soul out in my speech. I had no idea it would take off like that.”

The speech raised $1m for Bornstein’s organisation, which has since bought the lot where Tyler’s body was found as the first step to establishing a residential rehab centre.

It also alerted the Teamster leadership to the crisis among its members.

“Teamsters have taken this issue to heart because our membership, like the rest of society, is being plagued by the opiate epidemic,” said Michael Pryce-Jones, a senior governance analyst for the union.

Bornstein has backed the move to pressure McKesson and other drug distributors.

“It’s the absolute right thing to do to put the spotlight on these pharmaceutical companies who are chasing the almighty dollar and greed, and in return has got our whole country in a mess. I think it’s absolutely the right thing to do to put some pressure on these shareholders, put some pressure on these CEOs who are chasing money, to try to hold them accountable the best way we can,” he said. “Last year, doctors prescribed 700m opiates in the state of Ohio. Seven hundred million. That’s enough for 60 pills for every man, woman and child in our state. It’s unbelievable.”

McKesson has consistently denied any wrongdoing. It said it has set up extensive new mechanisms to prevent the delivery of opioids to pharmacies suspected of feeding the epidemic and is “aggressively working” to prevent pills being misused.

“We are doing everything we can to help address this crisis in close partnership with doctors, pharmacists, government and other organisations across the supply chain,” it said.

It also questioned the Teamsters’ motives.

“The recent efforts by the Teamsters labor union do little to address the root causes of the opioid epidemic. Nor can these attack efforts be disentangled from the labour contract dispute the Teamsters have been engaged in at one of our company’s facilities,” it said.

In a letter to Hall in November, the company said that accusations in lawsuits that it “flooded” the market with prescription opioids and that drugs are diverted to the black market are false because McKesson was delivering orders to licensed pharmacies.

Pryce-Jones said that does not absolve the company from verifying that the orders were legitimate given the prevalence of rogue pharmacies making large amounts of money from the epidemic.

“These companies have one task and that is the safe and secure distribution of drugs, particularly prescription drugs. Otherwise any courier company could do this role. They’ve been failing at that,” he said. “If these companies were doing their job right you shouldn’t be seeing blackmarket prescription painkillers.”

That’s a view shared by the former head of the DEA office responsible for preventing prescription medicine abuse, Joseph Rannazzisi.

In the mid-2000s, the DEA launched the “distributor initiative” to push McKesson and other companies to comply with obligations to report suspicious orders and to withhold deliveries they had doubts about. Rannazzisi said that executives at the distributors appeared receptive to the initiative.

“The response was, ‘Oh yeah, this is great. Thank you for telling us. We’re going to look at this closely. Yes, we understand.’ But in reality, nothing. They weren’t doing anything. They weren’t filing suspicious orders. They weren’t doing their due diligence. They were doing nothing. They weren’t listening to us,” he said. “I think they thought it was just another government programme that will go away given time. We noticed that even though we told them to look out for these things, and this is what’s happening, still no one was doing anything.”

Rannazzisi said it is incomprehensible that the drug distributors failed to notice surges in orders for opioid pills by some of the pharmacies responsible for feeding the epidemic.

In 2006, the DEA filed lawsuits against all three distributors. McKesson paid a $15m penalty in 2008 and promised to do things differently. The company said that in response it launched its Controlled Substance Monitoring Program and that it shared details with the DEA.

But Rannazzisi said the settlement paid by McKesson was a fraction of its profits and that it and the other distributors viewed it as little more than the cost of doing business and carried on as before. He also said they exerted political pressure in an attempt to get the DEA off their back.

The justice department filed another suit against McKesson in 2013 on behalf of the DEA and earlier this year the company paid $150m to settle the action. It did not admit guilt and said it paid “rather than engage in time consuming, contentious and expensive litigation”.

McKesson also said that it believed it had complied with DEA requirements after changing its delivery monitoring policies in 2008. “We had no reason to believe we were not meeting their expectations. McKesson was not told of any issues or problems with the CSMP until years later,” it said.

Rannazzisi said the distributors had not only a legal obligation but a moral one.

“A good corporate citizen has moral obligations to ensure the safety of the people they are supplying,” he said. “Corporations have no conscience. They’re not individuals. They’re not living breathing entities. They’re just these things with no conscience and all they’re driven by is making money. The fact is they were making a lot of money so why the heck are they going to change their way of doing business when they’re bringing all this money in?”

McKesson says it now has a “better partnership with the DEA” and has formed an Opioid Task Force. It also says it has “invested enormous amounts of time and millions of dollars” to establish a programme to detect suspicious orders and block deliveries.

But the company is still facing a growing number of lawsuits from states and municipalities. They include the small town of Kermit in West Virginia where McKesson is one of five companies being sued over the delivery of nearly 11m opioid dosages to a single pharmacy in a town with fewer than 400 residents.

Truman Chafin, the lawyer representing Kermit, questioned how the companies could not have known something was wrong.

“It wasn’t just Kermit. How can they send 423m pills to West Virginia with a population of 1.8 million and not know what they’re doing?” he said.