Uncategorized

Ernest Calloway, a Teamster Leader from St. Louis

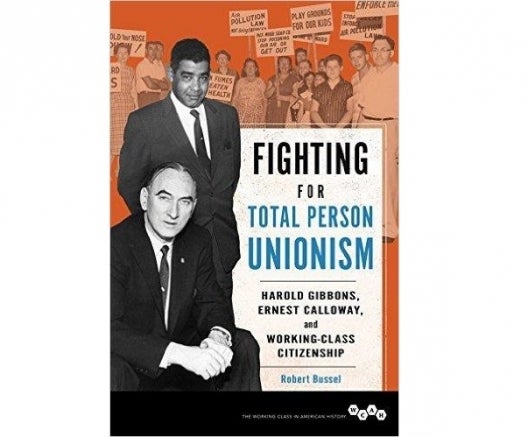

Ernest Calloway, a Teamster leader from St. Louis Local 688 is the subject of a new book about a unique aspect of the labor movement. Calloway, along with Harold Gibbons, principle officer of Local 688 and an International Vice President championed what they called “total person unionism” molding members into effective citizens in the workplace and the community. The book “Fighting for Total Person Unionism: Harold Gibbons, Ernest Calloway and Working Class Citizenship by Robert Bussel, chronicles their efforts.

Calloway was born in Heberton, West Virginia. His family moved to the coal fields of Letcher County, Kentucky in 1913 as one of the first black families in the coal mining communities of Eastern Kentucky. His father helped organize the first local United Mine Workers’ union in Letcher County. Calloway attended high school in Lynchburg, Virginia. He quit school and ran away to Harlem in 1925, during the time of the New Negro Renaissance. He worked as a dishwasher in Harlem until his mother fell ill, when he returned to Kentucky at age 17. Calloway worked in the mines of Consolidated Coal Company until 1930. During the early 1930s he traveled around the United States and Mexico as a drifter. After a frightening hallucinatory experience in the mountains of Baja, California in 1933, he returned to the coal mines of Kentucky.

That same year Calloway submitted an article on marijuana use to Opportunity the magazine of the National Urban League. Opportunity rejected Calloway’s manuscript but asked him to write another article on the working conditions of blacks in the Kentucky coal fields. Calloway submitted the second article “The Negro in the Kentucky Coal Fields”, and Opportunity published it in March 1934. The article resulted in a scholarship to Brookwood Labor College in New York, a training facility for labor organizers headed by the radical pacifist, A.J. Muste.

From 1935 to 1936 Calloway worked in Virginia and helped organize the Virginia Workers’ Alliance, a union of unemployed W.P.A. workers. In 1937 he moved to Chicago and organized railway station porters (redcaps) and other railroad employees into the United Transport Employees Union. Calloway helped write the resolution creating the 1942 Committee Against Discrimination in the CIO. When the first peacetime draft law came into effect in 1939, Calloway was the first African American to refuse military service because of race discrimination. The case received national publicity but was never officially settled. Calloway never served in the Jim Crow Army.

Calloway joined the National CIO News editorial staff in 1944.

In 1946 he married DeVerne Lee, a teacher who had led a protest against racial segregation in the Red Cross in India during World War II. The following year he received a scholarship from the British Trade Union Congress to attend Ruskin College at Oxford, England, but by the time it was granted, Calloway had returned to the United States and begun working with the CIO Southern Organizing Drive in North Carolina. Because of a dispute over organizing tactics in an attempt to unionize workers at R.G. Reynolds Tobacco Company, Calloway left the CIO in 1950 and returned to Chicago. There he was enlisted by Harold Gibbons of the St. Louis Teamsters union to establish a research department for the Teamsters in St. Louis.

Calloway canceled his Fulbright scholarship. He had discovered that Local 688 was creating programs for health, housing and recreation for its members, contributing as much to the social environment of workers as it did to adequate working conditions. In 1951 Calloway advised the rank and file union committee that developed a plan to integrate public schools in St. Louis. The Teamsters presented it to the St. Louis Board of Education three years prior to the Supreme Court decision on integration. The Board rejected the proposal.

In 1955 Calloway was elected president of the St. Louis NAACP.

Within the first two years of his presidency, membership grew from 2,000 to 8,000 members. He led successful efforts to gain substantial increases in the number of blacks employed by St. Louis taxi services, department stores, the Cocoa Cola Company and Southwestern Bell. The NAACP opposed a proposed city charter in 1957 because it did not include civil service reforms, public accommodations sections or support for civil rights. The charter was defeated.

Calloway served as campaign director for the Reverend John J. Hicks in 1959. Hicks became the first black elected to the St. Louis Board of Education. Calloway also directed the campaign for Theodore McNeal’s 1960 senatorial race. McNeal won by a large margin, becoming the first black elected to the Missouri Senate. The following year Ernest and DeVerne Calloway began publishing Citizen Crusader (later named New Citizen), a newspaper covering black politics and civil rights in St. Louis. Also in 1961 he was the technical advisor for James Hurt, Jr.’s successful campaign as the second black to be elected to the St. Louis School Board. DeVerne Calloway became the first black woman elected to the Missouri Legislature in 1962 when she won a seat on the House of Representatives on her first bid for public office.

Calloway worked with the Committee on Fair Representation in 1967 to develop a new plan for congressional district reapportionment. Supported by black representatives in the Missouri Legislature, and a coalition of white Republicans and Democrats, the plan created a First Congressional District more compatible to black interests. In 1968 Calloway filed as a candidate for Congress in the new district. He was defeated in the democratic primary by William Clay, who became the first black elected to Congress from Missouri.

In 1969 Calloway lectured part-time for St. Louis University’s Center for Urban Programs. He became an assistant professor when he retired as research director for the Teamsters in June 1973. He later became Professor Emeritus of Urban Studies at St. Louis University. Calloway suffered a disabling stroke in 1982.