The Early Years

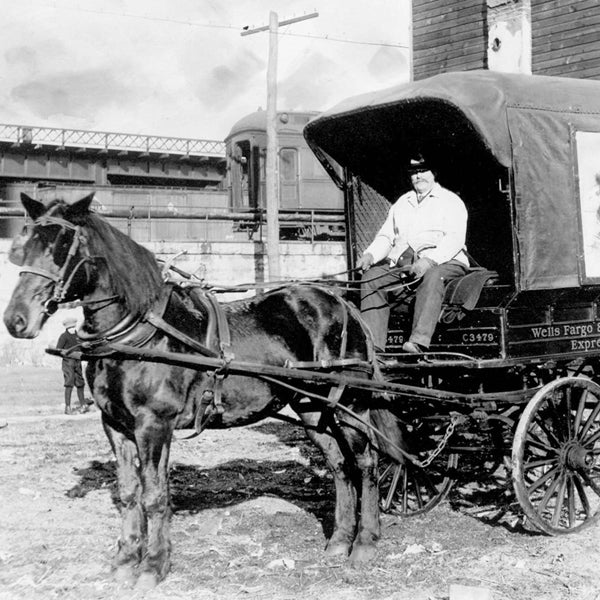

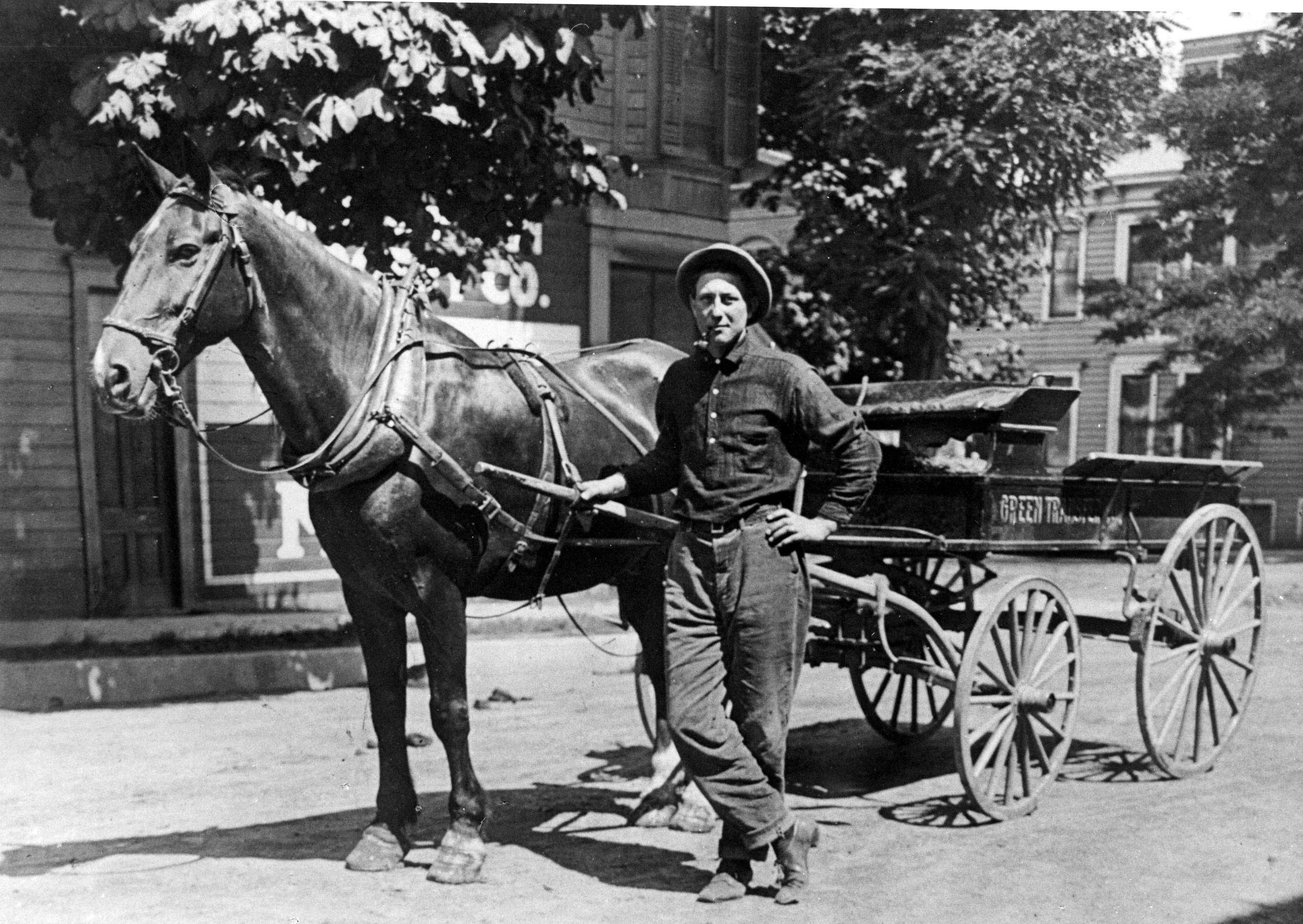

From colonial times to the turn of the last century, the men who drove horse-drawn wagons formed the backbone of North America’s wealth and prosperity. Despite their essential role as guardians of trade—the lifeblood of the economy—they remained unorganized and exploited.

In a teamster’s life, work was scarce, jobs were insecure and poverty was commonplace. In 1900, the typical teamster worked 12-18 hours a day, seven days a week for an average wage of $2 per day. A teamster was expected not only to haul his load, but to also assume liability for bad accounts and for lost or damaged merchandise. The work left teamsters assuming all of the risks with little chance for reward.

In 1901, frustrated and angry drivers banded together to form the Team Drivers International Union (TDIU), with an initial membership of 1,700. The following year, some members broke away, forming a rival group, the Teamsters National Union.

The Young IBT

Samuel Gompers, leader of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), was concerned by what he saw as a waste of resources and energy, and convinced the competing unions to meet and work out their differences. Agreeing that they were stronger in solidarity than separately, they re-joined forces to create the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) at a joint convention in Niagara Falls, N.Y. in August 1903. Cornelius Shea was elected its first General President.

The early IBT struggled. Labor laws were nonexistent, and companies used anti-trust laws against unions. In 1905, the IBT backed a bloody strike at the Chicago-based Montgomery Ward Company. The strike lasted more than 100 days, tragically took 21 lives, and cost about $1 million. In the end, Montgomery Ward’s cutthroat tactics broke the strike. In the face of this setback and other issues, the union realized changes were needed.

At the 1907 Convention, Dan Tobin, a strong young leader from Local 25 in Boston, was elected General President. His leadership, which would guide the Teamsters for the next 45 years, brought new momentum and vision to the fledgling union.

The Teamsters now entered into a period of aggressive organizing which resulted in a broadening of the membership base as well as increased revenue and recognition. And, the types of team drivers joining the union in large numbers expanded to include gravel haulers, beer wagon drivers, milk wagon drivers and deliverymen for bakeries. Teamsters would soon move into representing drivers of the new “motor trucks,” making them pioneers in the fledgling modern transportation industry.

A Guardian of Social Justice

As the Teamsters Union grew in stature and became more confident in its ability to protect members in the workplace, the success rate of its efforts increased. The union was winning strikes, contracts were becoming standardized and benefits were won that reduced hours and increased pay. The efforts of the union also began to bring about much deserved respect and a sense of dignity to its members for their contributions to society.

The Teamsters were also becoming known as leaders on issues of social justice. In 1912, the union set a precedent when delegates to the convention voted not to accept or allow any entertainment by non-union employees. Further, the union was one of the very first to recognize the importance of organizing women.

Teamsters also demonstrated openness to racial equality, being able to boast, “Teamsters know no color line.” By World War I, the Teamsters were on their way to being one of the most diverse organizations in the country.