Uncategorized

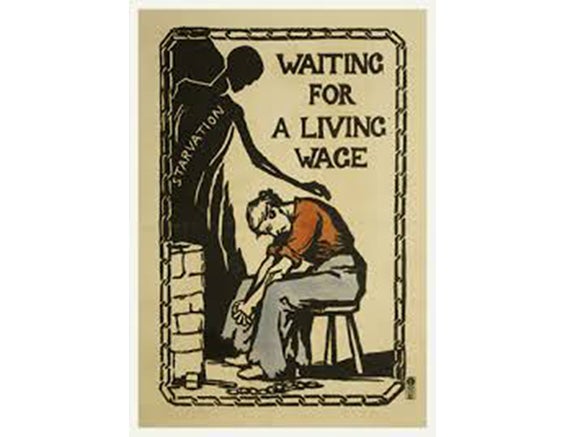

1913: Waiting For A Living Wage

|

|

President Wilson appointed William B. Wilson as his Secretary of Labor. Scottish-born Bill Wilson was a close friend of Tobin’s. As Secretary-Treasurer of the United Mine Workers (UMW), Bill Wilson had worked as a miner before being as elected for two terms as a Congressman from his Pennsylvania district. The UMW offices were near Teamster headquarters in Indianapolis, which also served as the city headquarters for a number of unions. |

On March 4, 1913 just a few hours before Woodrow Wilson took office, President William H. Taft signed into law the act that gave birth to the Department of Labor. Not much fanfare was given to this historical act due to it being the Inauguration Day for President Woodrow Wilson and all the activities associated with it.

President Wilson appointed a former coal miner and Secretary Treasurer of United Coal Miners, William B. Wilson, to serve as the first Secretary of Labor. Tobin admired Secretary Wilson and credited him with improving labor-management relations in the U.S., especially his work to enhance the plight of women and minorities in the workforce. Not to mention, of course, his strong support of labor unions.

The labor movement had begun a new chapter with Woodrow Wilson in the White House and, subsequently, Dan Tobin became more vocal – and more political – in his staunch advocacy for issues involving labor. On the political stage, Tobin was beginning to become a powerful voice for change.

During the Wilson years, Tobin would communicate a politicized message to the membership, which prior to the election of Woodrow Wilson had been rare within the labor movement. AFL President Gompers was wary of becoming too involved in politics, fearful it might hamper the union effort. Tobin, however, realized the power of having friends in Washington and began to pontificate with a political bent in his speeches and writings. Each month in the International Teamster, Tobin addressed the membership with a message of unity and activism. For Tobin, the push to become political was a way to tackle the issues of working people, which was reinforced by the Wilson Administration’s support of labor unions. It was becoming increasingly clear that when it came to political activism, the Democratic Party was where the Teamsters would need to galvanize their support.

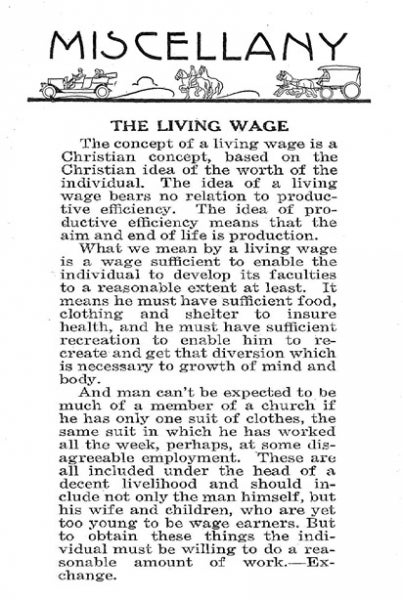

In Tobin’s mind, all workers not only deserved respect; they also deserved to live free from poverty. At the time, tens of thousands of fully-employed workers were still scraping to get by, forced to work gruesome hours in grueling conditions and still living in poverty. In his monthly column in April 1913, Tobin became one of the first to term the phrase “living wage.” In an article from the April issue of the International Teamster, Tobin explained the concept: “What we mean by living wage is a wage sufficient to enable an individual to develop its faculties to a reasonable extent at least. It means he must have sufficient food, clothing and shelter to insure health, and he must have sufficient recreation to enable him to recreate and get that diversion which is necessary to growth of mind and body.” To think that one hundred plus years later our members are still fighting for these basic rights is both humbling and troublesome.

In Tobin’s mind, all workers not only deserved respect; they also deserved to live free from poverty. At the time, tens of thousands of fully-employed workers were still scraping to get by, forced to work gruesome hours in grueling conditions and still living in poverty. In his monthly column in April 1913, Tobin became one of the first to term the phrase “living wage.” In an article from the April issue of the International Teamster, Tobin explained the concept: “What we mean by living wage is a wage sufficient to enable an individual to develop its faculties to a reasonable extent at least. It means he must have sufficient food, clothing and shelter to insure health, and he must have sufficient recreation to enable him to recreate and get that diversion which is necessary to growth of mind and body.” To think that one hundred plus years later our members are still fighting for these basic rights is both humbling and troublesome.