Uncategorized

1915: Life in Indianapolis

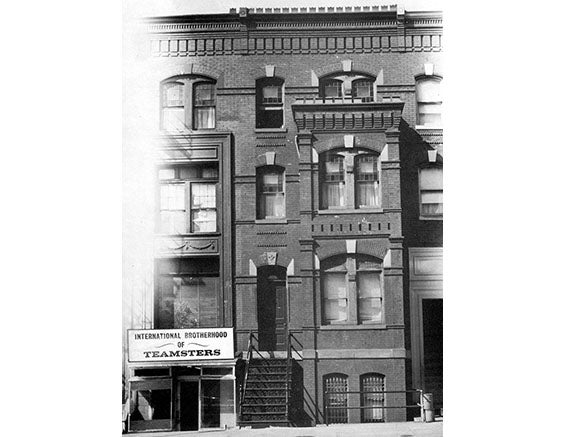

The International Headquarters in Indianapolis was a modest building with only a few employees, including General President Tobin and General Secretary-Treasurer Hughes. Tobin and Hughes worked in lockstep to grow the union nationwide. Both men were extremely proud that the International was financially secure, and both men are credited with putting the finance system in place that is still in use today. After years of financial struggle, the Teamsters Union had finally found its footing thanks to the young General President’s forward-thinking vision for the union.

By 1915 the treasury was the soundest it had ever been, noted Tobin at that 1915 convention, adding: “Our local unions have the largest degree of autonomous rights of any local unions in the American Federation of Labor. We permit you under our present laws, to hold in your local treasuries at least 90 percent of the money you collect from the membership. Many organizations of labor take at least 50 or 60 percent of the total collection from the membership into the International Treasury.”

|

|

Tom Hughes holds an orphan at an annual picnic for the Children’s Home in Indianapolis. Hughes involved the Teamsters in all kinds of community service and charity work, laying a foundation that lasts to this day. |

Although Tobin received the lion’s share of the credit, the success of the treasury was mostly due to the oversight of the young Secretary-Treasurer. Hughes’ keen oversight and wise approach to spending began in 1906, when he was elected to the second highest position in the union. Years of poor decisions and frivolous spending by Tobin’s predecessor, Cornelius Shea.

While Hughes became an active resident of Indianapolis, involving himself in community service and charity work for the city, Tobin preferred his privacy. He spent his hours outside the office reading and writing in his small, dimly-lit room at the Indianapolis Grand Hotel for $2.50 a day, corresponding in letters and telegrams with other prominent labor leaders like AFL President Samuel Gompers and UMWA President John L. Lewis over issues facing the union effort.

He would also write home to his wife, Anne, and their six children, all of whom were still living in Massachusetts. The guilt of being away from his family weighed heavy on Tobin throughout the decade. Although he traveled from Indianapolis to Boston as much as possible, travel in those days was not a plane ride away and, therefore, his visits could be infrequent depending on the demands of the union.

Involved in so many things with little time and attention to spare, Tobin chose a style of management which heavily relied on others. Like all good leaders, Tobin kept close people he could trust. He eschewed frivolous activities, avoiding “picayune” correspondence and saving his time for high-level matters while delegating authority to run day-to-day operations to competent subordinates at the International: experienced men such as Michael Casey, George W. Griggs and Michael Cashal. However, it was his hand-picked organizers who he relied on most, demanding comprehensive reports from them while in the field. The most trusted of his International Organizers was old friend and fellow Bostonian, John Gillespie, their time together leading Local 25 lasted and grew with each passing year of Tobin’s presidency. As Tobin’s most trusted confidant, Gillespie served as his eyes and ears in the field, helping to aide in major decisions and informing the International of organizing and bargaining efforts of locals nationwide. Gillespie, still headquartered out of Boston when not traveling, would also look out for Tobin’s wife and family while Dan was away in Indianapolis.

Also in 1915:

The war, at least initially, had a negative effect on American workers. Unemployment across the country increased significantly in 1915. In the February issue of the International Teamster, Tobin maintained “there must be something wrong with our civilization when the able-bodied, millions of workingmen can find nothing to eat; when innocent children and faithful honest mothers are forced to starvation.” He predicted that the situation would only get worse unless “we control the balance of power in our legislative chambers” so as to give workers their proper due.

With millions dying overseas, Tobin and eight other international union leaders met on May 27, 1915, to oppose American war preparations. Unwilling to actually oppose war, the group asked Gompers to form a committee to enunciate labor’s stand on the European conflict. The committee would meet several times in the two years leading up to America’s entrance into WWI.