Headline News

1919: The Delegate

|

|

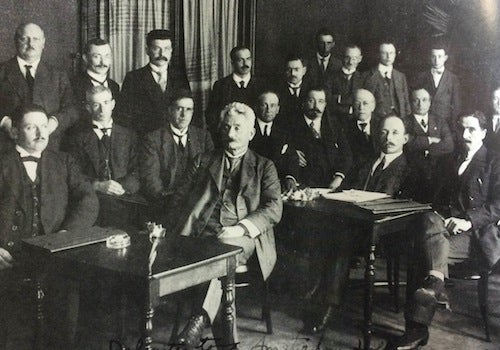

Delegates to trade union convention in Amsterdam, Holland, 1919. Tobin is seated in the 3rd row, 3rd from right. Samuel Gompers is 3rd row center |

Throughout the war, AFL President Samuel Gompers served by President Woodrow Wilson as representative to the Advisory Committee of the Council of National Defense (1917 to 1919), on which he helped to establish an unprecedented wartime labor policy that clearly laid out government support for independent trade unions and collective bargaining. At the war’s end, Wilson appointed AFL President Samuel Gompers to the Commission on International Labor Legislation at the Versailles Peace Conference, where Gompers helped create what would become the International Labor Organization (ILO).

|

|

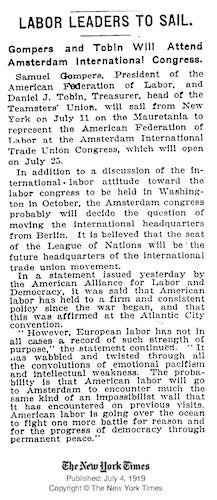

The New York Times declared in the summer of 1919: “Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor, and Daniel J. Tobin, Treasurer, head of the Teamsters’ Union, will sail from New York on July 11 on the Mauretania to represent the American Federation of Labor at the Amsterdam International Congress.” |

In 1919, Gompers chose Tobin as the AFL’s second delegate to the founding convention of the International Federation of Trade Unions. Restarting the conference after the war was not a simple matter. Although peace agreements had been signed, in the minds of attendees, the war was not completely over.

In his unpublished memoirs, Tobin writes of his second trip abroad in vivid detail:

Shortly after the Treaty of Versailles, a meeting was called in Amsterdam, Holland. Sam Gompers and I were chosen as the representatives of the American Federation of Labor to attend. Much as we were anxious to help over there, we were more anxious that the conditions of labor be safeguarded and protected in our own country.

Gompers and I stayed over in England for a few days in consultation with the British Labor Leaders, many of whom were coming to Amsterdam for the conference. We decided that we would work together in the convention … The labor politicians in Europe were very clever and very able. They knew world history and political entanglements much better than our American Trade Unionists. They make it a study from their infancy and they very craftily introduced a resolution blaming the American capitalistic system for the war. When this resolution was introduced condemning American capital and indirectly condemning our American government, which they always claimed was the tool of capitalism, I had a conference with Gompers; and being somewhat outspoken then as I have been all my life, I saw the danger and I immediately told Sam that I would not attend the conference unless the resolution was withdrawn, that I was an American and that I knew what brought about the war and that this was an insult to American Democracy … Sam had been entertained by everyone although slightly ignored by the German leadership because they hated the Jews. Sam had not been giving too much attention to the many things that came before the convention as he should and I did not blame him because he was a very busy man. We were both appointed on several important committees. I was a member of the committee to which this resolution was referred. Sam advised me to go slow and be careful – that we could not break up the conference … Sam finally saw the point I was making and decided that we would stick together and it was agreed between us that he, as President of our American FL would get up on the floor at the next session of the conference and make a the statement that America was forced into the war by the actions of Germany in skinning our ships without the semblance of apology and in defying us to enter the war, and that we resented such a declaration as contained in the resolution that American and British Capital was responsible for the war. Immediately English delegates sided with America, as did Belgium and France, and the resolution condemning American capital and American government was withdrawn.

How happy and elated I was that evening.

Much to Tobin’s dismay, the incident, although pivotal in the European labor movement, did not receive much press coverage:

Has this ever been referred to by any of our American newspapers?—no. The English press referred to it and commended the American delegates but very little attention was paid to it by the press of the UnS. We defended the US government, two Americans, labor representatives, before a gathering of the Europeans which had a lasting effect on the mind of the trade unions of many other counties, including Germany, for many years to come.

Tobin then chronicles an even more eventful story from the journey, their return voyage home:

Having laid the foundation of the International Federation of Trade Union, we left Amsterdam and decided to meet later on and sail back together from Liverpool. I went over to Ireland to see some my father’s relatives while Gompers visited France. Tobin and Gompers met again in Brest, where American Military Forces had control of the port city.

Gompers, our secretaries, and I were the only civilians aboard. We were due to arrive in New York in eight days but according to the speed of the ship it would take at least nine or ten days. Mr. Gompers and I were arguing the cause of the slow passage when the Captain of the ship, a wonderful gentleman, came to the door and wondered what we were discussing with such earnestness. He told us there was a spontaneous combustion fire in one of the coal pockets. “Oh,” he said, “don’t be alarmed; it is perfectly safe.” They were carrying 2100 tons of coal in that ship and in each pocket there was about 700 tons in the middle pocket had caught on fire from a spontaneous combustion.

I did not feel that it was anything to be happy about, but I must say that it worried Mr. Gompers, as it should. “Of course,” the Captain explained, “there are very heavy steel jackets separating each coal pocket.”

At night we would play cards for a few French francs, which were not worth very much. A franc was then 2 ½ cents. During the evening I would say to Sam, in order to have some fun, “Well, there is no use in us going to bed; this foolish ship may blow at any time.” Sam was nervous and I now regret that I was just having some fun with him and that I somewhat disturbed his mind because, after going to bed (we were in opposite beds in the same room) Sam could not sleep and he would wake me up at two or three in the morning. The sea was perfectly calm but we were going very slow. I remember saying to him one night, when I wanted to have some more with him, “Well, Sam, this is not a very pleasant bed to sleep in, but there is a big fire down below and you know, Sam, steel can melt with heat.” He would get up, walk around, try to read something and it was sometime afterwards when I realized that I should not have said those things; the truth of the matter, though, was that this was a possibility. At any rate, we came into NY after ten or eleven days at sea, about three days late. The ship was unloaded, the coal was taken off, hose-water pressure was used on the fire, and in five days the fire was extinguished. Not one word about this affair was ever published in any paper. As a matter of fact, the Captain said no one knew of this condition on the ship with the exception of the inside members and officers of the crew and he pledged us to secrecy. This experience I have never repeated until now.

Tobin summarizes the affair years later, lamenting over the inevitable failure of the League of Nations:

“History should emphasize the fact that the defeat of the Treaty was the greatest crime that was ever committed against the freedom of the world. If the United States had been a party to the League of Nations, the Second World War may have never come to pass. The Treaty tried to carry on, with England, France and Italy, the safeguards needed to prevent another world war,” wrote Tobin years after the League of Nations had failed, courtesy of “a partisan Congress hell-bent on defeating any measure proposed by President Wilson.”

Following the war, Tobin emerged as a preeminent U.S. labor leader, and the IBT’s position in the vanguard of the U.S. labor movement was cemented.