Uncategorized

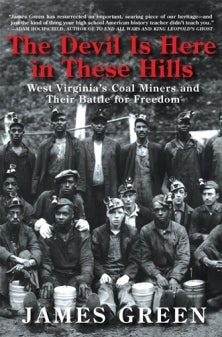

The Devil Is Here In These Hills” Review”

The current assault on workers’ rights is the latest chapter in a long and ugly history. In that history, the battles that raged across southern West Virginia in the early 20th century stand out as among the most vicious labor conflicts in the American past. Operators in the nonunion coalfields resolved to keep their mines union free, employing an arsenal of weapons to maintain the upper hand. The results were brutal. Appalachian coal country, one writer observed, was “an American heart of darkness.”

Historian James Green vividly recreates this world in his compelling new book, “The Devil is Here in These Hills.” West Virginia miners’ list of grievances was long and depressing. Many lived in company towns, where owners’ complete control made a mockery of democratic rights. Wages were low; working conditions were horrific, with accidents regularly taking the lives of hundreds of men and boys. Efforts to challenge the industrial order were met by brute force.

Those conditions and miners’ determination to challenge them turned the region into a virtual war zone. Baldwin-Felts detectives, vigilantes and state militiamen occupied communities and broke strikes; blacklists and yellow-dog contracts routed out union organizers.

Declarations of martial law empowered military officials to arrest and hold hundreds of trade unionists without charge. During a “mine war” in 1920, military officials banned the state’s labor newspaper and police arrested anyone caught reading it.

“The big advantage of this martial law is that if there’s an agitator around you can just stick him in jail and keep him there,” explained one government official. “Justice is dead, freedom is a thing of the past, and liberty is but a dream of the future,” a local labor journalist concluded.

The book is “more than another gruesome chapter in the history of American violence,” Green argues. It is “the story of a people’s fight to exercise freedom of speech and freedom of association in workplaces where the rights of property owners had reigned supreme.” He recounts the efforts of countless men and women to contest the mine owners’ reign of terror. But their challenges proved no match for the power of the mine operators and their allies in state government.

Until, that is, the coming of the New Deal. A changed political environment, one that was far less anti-labor than the one that preceded it, allowed a revitalized United Mine Workers of America in 1934 to organize West Virginia’s miners, win union recognition and engage in collective bargaining. Wages rose; working hours fell; safety improved; and the reign of armed company guards came to an end. The “Bill of Rights finally had real meaning to the people who lived and worked in the coal country of West Virginia,” Green concludes.

What West Virginia’s miners “could not have understood at the time was that their struggle would broaden and deepen the meaning of freedom in all of industrial America,” Green tells us. In the current anti-labor climate, the lessons Green recounts are well worth remembering.

Eric Arnesen is the James R. Hoffa Teamsters Professor in Modern American Labor History at The George Washington University