Headline News

Civil Rights and the Labor Movement: A Historical Overview

Eric Arnesen

The George Washington University

Anyone familiar with the labor movement today knows that organized labor is a heterogeneous group – African Americans, Latinos, Asians and Asian Americans, whites, men and women, citizens and undocumented workers all make up the ranks of the unions affiliated with Change to Win and the AFL-CIO. There is no question that the American labor force is characterized by unprecedented diversity – and, not surprisingly, organized labor is as well. In recent years, the labor movement has come to embrace and, to an unprecedented degree, champion racial and gender equality, often putting it at the forefront of movements for equality and civil rights in the United States. And that connection – labor and civil rights – has deep historical roots.

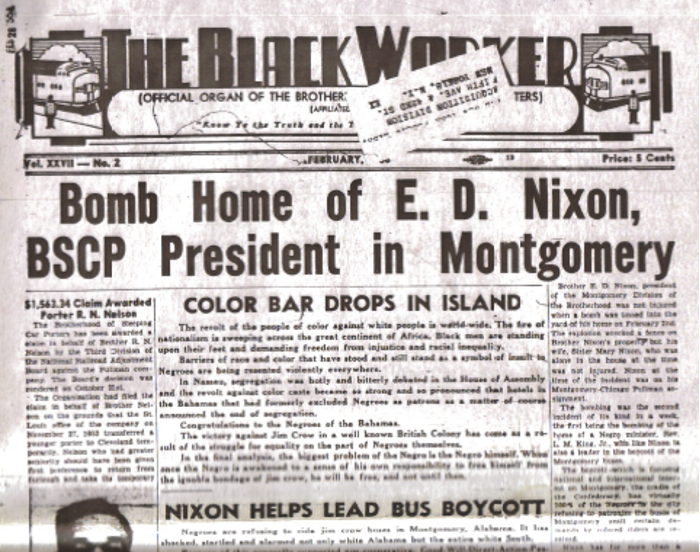

Take one of the key moments in the emergence of the modern civil rights movement: The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56. The standard story features a tired seamstress, Rosa Parks, whose courageous refusal to give up her seat on a segregated public bus launched a boycott and a movement. That narrative also features a young Martin Luther King, Jr., a then-obscure young minister whose political career on the national and international stage was launched by his leadership of the boycott. But the boycott’s origins lay elsewhere, in part with a trade unionist, E.D. Nixon, a local civil rights activist who was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. It was Nixon who approached the newcomer King to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association; trade unionists in the North offered substantial financial and logistical support to the boycott; and, from the perspective of the Pullman Porters, the boycott was theirstory which they covered in detail in the pages of the Black Worker, the porters’ monthly journal.

Think back almost half a century to 1963 when a quarter of a million people gathered on the National Mall before the Lincoln Memorial in the great March on Washington. Present that day were tens of thousands of trade unionists, whose numbers, funding, logistical assistance, and moral support helped make this an historic success. The initial organizers of the march were the civil rights and labor legend, A. Philip Randolph, and his assistant, Bayard Rustin. Randolph was at the time the most important black trade unionist in the nation, a man considered to be the “dean” of the civil rights movement; Rustin would go on to work with the AFL-CIO for years to come. And the purpose of the march? That was captured in its slogan: Jobs and Freedom. This demonstration was not simply about civil rights broadly construed, particularly the abolition of segregation across the land. It also had an economic dimension, and the “jobs” demand rested on an understanding that all American workers, black and white, needed access to employment, something, organizers argued, that the government was responsible for ensuring.

Also think back to the 1968 sanitation strike in Memphis, Tennessee. In that very southern city, the revolution brought about by the civil rights movement may have won a modicum of desegregation and voting rights, but it left untouched a racial division of labor that rested upon black subordination and exploitation. And, in that fateful year, sanitation workers affiliated with American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), went out on strike against a city that forced them to work without dignity, decent wages, or representation. The strike proved controversial in Memphis but attracted the support of trade unionists around the country, as well as the support of the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., who was assassinated while in town on the strikers’ behalf. At that moment, the labor movement was a civil rights movement, the sanitation workers’ union a vehicle not merely for wages and better working conditions but for civil and human rights as well. In subsequent years, the labor movement slowly but decisively committed itself to civil rights. That’s not to say there wasn’t controversy or a difference of opinion about how, precisely, to achieve those rights. But at a time – the 1980s and 1990s – when currents in American politics were running against the civil rights tide, the labor movement was putting itself squarely in the camp of racial equality.

This wasn’t always the case. As late as the 1940s, the African-American scholar Rayford Logan simply and directly declared: the “‘solidarity of labor’ is [just] another myth as far as the history of American labor is concerned.” Discriminatory white unions, particularly in the American Federation of Labor (AFL), were ubiquitous in pre-World War II America. In Logan’s eyes, they deserved the same epithet that they directed at Big Business: they were merely “soulless corporations.”[1] The overall record of white unions was not impressive: From Reconstruction to, in some instances, the 1950s and 1960s, numerous unions worked to exclude blacks from key sectors of the labor market or otherwise restrict them to the least desirable jobs. And that sorry record accounted for blacks’ traditional antipathy toward organized labor.

The era in which many trade unions excluded or discriminated against black and other minority workers came to be known as the “nadir” for African Americans, in Rayford Logan’s term for the late 19th century. Many of the gains made during Reconstruction had been rolled back or wiped out: Disfranchisement stripped black men of the vote in many southern states; Jim Crow laws mandated the legal segregation of the races; and white violence – terrorism, actually – against African Americans intensified.

For the century after the Civil War, sharp and enduring barriers restricted the employment opportunities of racial minorities in the United States. In the aftermath of slavery, discrimination in employment on the basis of race was widespread and a sharp racial division of labor divided the American labor force. “In the half century that the negro [sic] has had the franchise as the crowning of his freedom,” one New Jersey newspaper concluded in 1920, “he has, by and large, been relegated to the role of a hewer of wood and a drawer of water. . . Theoretically free, the negro has not been able to sell his labor” – except for a few exceptions – “where most he wanted to.”[2] The white Progressive-era journalist Ray Stannard Baker turned his attention to the “color line” in the early 20th century. “As I traveled in the North,” he reported, “I heard many stories of the difficulties which the coloured man had to meet in getting employment. Of course, as a Negro said to me, ‘there are always places for the coloured man at the bottom.’ He can always get work at unskilled manual labour, or personal or domestic service – in other words, at menial employment.”[3]

Outside of the agricultural sector, black labor was largely confined to unskilled work and domestic service. Conditions in rural, isolated lumber or turpentine camps were generally harsh; labor on the docks of the Gulf Coast or South Atlantic was arduous; coal mining deep in the earth in Alabama, West Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky was difficult and dangerous. “The fetters were no sooner removed from the limbs of the black slave than the fetters of condition took their place,” the New York Freeman observed somewhat hyperbolically in 1886. Today, “it is a painful and notorious fact that the last condition of the common laborers of the South is, in many respects, much more degrading and demoralizing than the first. . . . The colored people of the South are gradually, as a class, sinking deeper and deeper into the cesspool of industrial slavery.”[4]

How, precisely, were African Americans to respond to this state of affairs? How did they respond? Booker T. Washington, the conservative head of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, championed “industrial education,” hard work, and an avoidance of electoral politics; he lectured black workers to avoid unions, ally with white industrialists, and even break strikes to secure jobs otherwise closed to them. W.E.B. Du Bois emerged in the early 20th century as Washington’s chief opponent, a champion of classical education, civil rights, and political engagement on behalf of black Americans. By the World War I era, Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association dismissed civil rights as hopeless and promoted a black nationalism centered on black business, pride, and an eventual return to Africa; he too opposed unions and promoted black capitalism. And Ida B. Wells along with the black clubwomen’s movement highlighted anti-lynching activism and racial uplift.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries also witnessed the emergence of a small but significant black labor tradition. Despite white labor’s racial practices and beliefs, a visible minority of black southerners found in unionization a means to pursue the same goals as white workers: raising wages, shortening the working day, and improving on-the-job conditions. Their efforts also reflected a quest for workplace dignity and a modicum of respect – or at least a lessening of brutal treatment – from white managers. Domestic workers in Atlanta, dock workers in Houston, Galveston, New Orleans, and other Gulf and South Atlantic ports, coal miners in Alabama, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, timber workers in Louisiana and East Texas and lumber workers in North Carolina – all turned to unions between the 1870s and the 1950s to advance their interests in an economically inhospitable environment. Similarly, smaller groups of black workers – oyster shuckers, washerwomen, phosphate miners, railroad car cleaners and firemen, sugar harvesters, hod carriers, bricklayers, carpenters and joiners, and teamsters, to mention just a sample — organized their own locals. Some affiliated with the Knights of Labor, the AFL, or the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), while others remained independent.[5] As two scholars recently put it, the “quest for economic justice defined some of the most challenging, imaginative—and underappreciated campaigns” engaged in by blacks to improve their “life conditions.” [6]And unions were one major vehicle in that quest for economic justice.

Some unions welcomed them – or at least accepted them into their ranks. The Knights of Labor in the 1880s, the Industrial Workers of the World in the early 20th century, and the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1930s and 1940s all advanced a vision of a unified working-class, one whose divisions along lines of color, creed, political belief, and gender paled before the power of workers’ common interests. Even the American Federation of Labor, with its largely skilled, white craft unionist base, enlisted substantial numbers of black workers – at least in some trades.

If the black labor tradition represented an important current of black protest and workplace activism, its numbers and impact should not be exaggerated, at least in the decades before the late 1930s and 1940s. The vast majority of African American workers, north and south, remained outside of the industrial labor force and outside of the ranks of organized labor at least until the Great Depression and World War II years. Even the Great Migration of the World War I era, which brought as many as half a million African Americans to the North during the war and another 700,000 during the 1920s, did not fundamentally alter the relationship between the larger labor movement and African American workers. Although some black migrants joined unions during the war, most did not. And many white unions didn’t want them.

Yet black migration produced a new kind of black politics during and after the era of World War I. The newcomers did not discover a “Promised Land” in the North; rather, they encountered employment and housing discrimination and, at times, significant white violence. They did manage to gain access to some employment in the North’s mills and factories, jobs that had previously been closed to them, thus achieving a foothold in modern industry.

By the Great Depression of the 1930s, the migration and the increased black urbanization it fostered had significant consequences. Growing numbers of migrants in the North translated into new resources and new attitudes, laying a firm economic basis for an increasingly solid infrastructure of businesses, churches, and political organizations. More people meant more consumers for black owned businesses, black periodicals, and cultural institutions as well as expanding political influence and the emergence of a more aggressive style of black protest politics that placed civil rights squarely on the agenda of labor unions, municipalities, and the federal government. These changes did not happen overnight. By the 1920s and certainly by the Great Depression, new and visibly militant organizations were appearing. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, founded in 1925, fostered a new openness to unionization in black communities and spearheaded a far more aggressive approach to protest, an approach that pushed the then somewhat more staid National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) into a more confrontational stance. That was just the beginning. The 1930s witnessed the blossoming of Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work campaigns designed to break down job barriers and the emergence of the National Negro Congress, a heterogeneous organization that supported unionization and community protest. These organizations pioneered militant styles of protest politics that involved considerable grassroots mobilization and confrontation with established authorities. During World War II, activists participated in various “Double V” campaigns – calling for a victory over fascism abroad, and a victory over racism at home.

A vital part of this upsurge in black protest involved union organizing. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), formed in 1925 by Pullman Porters, was at the forefront of a tremendous shift in black public opinion toward a pro-union stance. For a decade, A. Philip Randolph and his colleagues in the BSCP fought an uphill battle against the powerful Pullman company which unleashed a barrage of hostile attacks against the fledgling union, relying upon spies and informants and harassing and firing known union activists. Yet the Brotherhood survived and eventually triumphed. Over the course of the late 1920s and early 1930s, the BSCP reached out to black community and religious leaders as well as to white liberals, continuously spreading the gospel of black trade unionism. When the BSCP launched its crusade for recognition in 1925, it confronted a black elite that was largely, if not entirely, indifferent or hostile to unions. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Randolph cultivated NAACP officials, clergymen, and black women’s clubs. The result was an historic shift in opinion of the black middle class from anti- to pro-union.[7] In 1935, the BSCP prevailed, decisively winning a government-supervised union representation election.[8] Two years later, in 1937, it negotiated an unprecedented and path breaking contract with the Pullman company that constituted, in Randolph’s words, “a foundation on which the future of the porters’ well-being and a constructive and powerful Brotherhood” could be built.[9]

The porters’ victory, Randolph believed, would reverberate far beyond the ranks of Pullman employees. “It should serve as one great stimulant to the organization of Race workers in all industries throughout the country…. [T]he Race has the courage, the spirit and the will to fight for economic freedom and justice like all other workers.”[10]

Unionism spread well beyond railroaders’ ranks. The AFL had large numbers of black workers in some international unions (the longshoremen, mine workers, and Teamsters in particular). And with the emergence in the mid-1930s of the CIO came a union federation committed to industrial unionization and the organization of black workers. In much of basic industry – automobile manufacturing, steel, rubber, meatpacking, and the like – the CIO succeeded, by the early 1940s, in winning union representation elections and attracting substantial black support. That’s not to say that discrimination vanished from organized labor’s ranks; it hadn’t. But it is hard to dispute this simple fact: One sector of the labor movement had dropped some of its exclusionary barriers and welcomed black participation, and African-Americans had responded accordingly, shifting decisively toward a pro-union stance. By 1943, some 400,000 African American workers had joined the labor movement.[11]

Perhaps the most notable, and important, initiative of this new labor-based civil rights movement was the wartime March on Washington Movement, a brainchild of A. Philip Randolph that aimed at overturning segregation and exclusion in the armed forces and discrimination in defense industries. As military production picked up in 1940 and 1941, unemployment rates for white workers dropped noticeably. But African Americans were largely excluded from this economic recovery. Randolph called for 10,000 African Americans to descend upon Washington, D.C. in a “pilgrimage” to “wake up and shock official Washington as it has never been shocked before.”

“If the Negro is shut out of these extensive and intensive changes in industry, labor and business” prompted by the war, he charged, “the race will be set back over fifty years.” “WE LOYAL NEGRO AMERICAN CITIZENS DEMAND THE RIGHT TO WORK AND FIGHT FOR OUR COUNTRY,” his MOWM declaration insisted.[12] The numbers of projected protesters kept increasing. First, 10,000. Then, 50,000. Finally, 100,000. Black journalists talked of a “mammoth mass demonstration” bringing together African Americans from “the voteless South and the jobless North, united in protest over a way of life which offers neither freedom nor opportunity”; they would “invade” the nation’s capital, that “fountain head of racial prejudice,” a city that “seethes with demoniac racialism.”[13] If African Americans could not stop discrimination outright, they could, nonetheless, one black periodical put it, “tear the mask of hypocrisy from America’s democracy.”[14]

The March on Washington Movement’s goal was to force the hand of the administration of Franklin Roosevelt. “I can’t afford to permit you to bring 100,000 Negroes to Washington,” the president informed Randolph, “because there is no way to manage a tremendous group . . . such as that. You can never tell what might happen, nor can I.” But administration efforts to have Randolph call off the march went nowhere. In the end, the president blinked first. FDR backed down. At the eleventh hour, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802 and Randolph called off the march: There shall be “no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, color, or national origins,” the order boldly declared. To ensure that the policy of non-discrimination by employers, labor unions, and the government was carried out, the order created a Fair Employment Practice Committee to collect information, investigate complaints, and take “appropriate steps to redress grievances.”[15] Although the serious matter of segregation in the armed forces remained unaddressed, Randolph declared the order the “greatest thing for Negroes since the [E]mancipation [P]roclamation.” The fight against discrimination, he claimed, “will help to cleanse the soul of America of the poison of hatred, antagonism, and hostilities of race, color and national origin, and strengthen our country’s foundation for national unity and national defense.” [16]

The Executive Order was no Emancipation Proclamation. The FEPC did not eliminate discrimination in American industry and Randolph knew it. The agency possessed few resources and little power to compel compliance with the Executive Order. Black grassroots activists rallied behind the beleaguered federal agency with conferences, pickets, marches, and mass demonstrations in churches, auditoriums, parks, union halls, and streets around the nation during the war.[17]

On one level, these activists failed. The FEPC did not survive the war, for its congressional opponents simply cut off its funding. Randolph’s new National Council for a Permanent FEPC held rallies and marches and lobbied Congress, but did not accomplish its goal of extending the FEPC’s life. Although individual states passed weak fair employment acts, the federal government did not.[18]

On another level, however, these activists succeeded – if we take a longer view. They managed to place the issue of employment discrimination squarely on the political agenda, where it would remain for the next two decades and beyond. Fair employment, for the first time, became a rallying cry, a program around which African Americans and whites – civil rights organizations, trade unions, and federations of Christians and Jews — could and would organize for years to come. Eventually, they prevailed. The passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, particularly its Title VII, finally outlawed discrimination in American workplaces and in union ranks.

Before and after the passage of the 1964 Act, African-American trade unionists challenged the House of Labor to live up to its creed. Both the AFL and CIO tolerated a wide range of racial policies among its constituent unions. While some unions accepted black members and accorded them a degree of respect and equality, others did not. Again and again, Randolph and other black union activists called upon organized labor to ban discrimination outright in its ranks, end all racial restrictions on union membership, and abolish inferior, segregated “auxiliary” unions. The AFL “cannot say it is democratic unless it cleans its house and says that, regardless of race, color and creed, any worker can join any A F of L union,” the president of the BSCP charged in 1942.[19] As black disaffection with the AFL-CIO grew and the struggle for civil rights expanded across the South, the federation finally adopted a civil rights program at its 1961 convention that broke, somewhat, with past practice.[20]

By the early 1960s, many union internationals offered crucial support – moral, financial, and organizational – to the push for civil rights legislation. Tens of thousands of those present at the 1963 March on Washington were trade unionists. That demonstration for “Jobs and Freedom” raised fundamental economic issues, calling not only for desegregation but for passage of a federal fair employment practices act, a higher minimum wage, and a serious public works program. Randolph and other union activists maintained that equality for African Americans required both civil and economic rights, that progress for black Americans required not only the passage and enforcement of civil rights and anti-discrimination laws but economic policies designed to ensure the economic health of black Americans.

The history of the civil rights movement – perhaps the word movements is more appropriate – is a rich, long, and complicated one. That history cannot be reduced to simply its modern phase; nor should it be reduced to its most famous figure, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The history of the labor movement is a rich, long, and complicated one as well. The labor movement, once an obstacle to black economic advancement, is now an ally of the civil rights movement. Black workers – and other minority workers – refused to accept the labor movement’s racial bars. In fact, the labor movement was never the sole property of white workers. In countless instances African Americans turned to unionization for their own purposes to pursue both an economic agenda and a civil rights agenda. And, in so doing, they transformed both the labor movement and the civil rights movement. It is not much of an exaggeration to conclude that, in the process, they helped change a nation as well.

[1] Rayford Logan, “The Negro Wants First-Class Citizenship,” in Rayford W. Logan, ed., What the Negro Wants (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1944), 12.

[2] “Labor and the Color Line,” Newark Evening News, May 14, 1920, in Tuskegee Institute News Clipping File, Reel 11, Frame 0728.

[3] Ray Stannard Baker, Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy (New York: Doubleday, Page, 1908), 131.

[4] “Industrial Slavery in the South,” New York Freeman, December 25, 1886; also see “Colored Men, Reflect,” New York Freeman, December 4, 1886, reprinted from John Swinton’s Paper.

[5] On traditions of black unionization, see: Eric Arnesen, “Following the Color Line of Labor: Black Workers and the Labor Movement before 1930,” Radical History Review No. 55 (Winter 1993): 53-87; Tera W. Hunter, To ‘Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors After the Civil War (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997). For a sample of the literature that addresses black unionization in the South, see: William P. Jones, The Tribe of Black Ulysses: African American Lumber Workers in the Jim Crow South (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005); Peter J. Rachleff, Black Labor in Richmond 1865-1890(1984; Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988). Classic works that retain considerable value include: Classic works on the subject include: Charles H. Wesley, Negro Labor in the United States 1850-1925: A Study in American Economic History (New York: Vanguard Press, 1927); Sterling D. Spero and Abram L. Harris, The Black Worker: The Negro and the Labor Movement (1931; rpt. New York: Atheneum, 1969); Horace R. Cayton and George S. Mitchell, Black Workers and the New Unions (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1939).

[6] Charles M Payne and Adam Green, “Introduction,” in Payne and Green, eds., Time Longer Than Rope: A Century of African American Activism, 1850-1950 (New York: New York University Press, 2003), 2-3.

[7] Beth Tompkins Bates, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925–1945 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 81-86.

[8] T. Arnold Hill, “Labor: The Pullman Porter—The Big Boss,” Opportunity XIII, No. 6 (June 1935), 186; The Crisis (August 1935), 241; New York Age, July 6, 1935.

[9] A. Philip Randolph, “Brotherhood and Pullman Company Sign Agreement,” The Black Worker III, No. 7 (October 1937): 1.

[10] Minneapolis Spokesman, July 5, 1935.

[11] Oklahoma Black Dispatch, March 25, 1937.

[12] “A. Philip Randolph,” Chicago Defender, February 1, 1941.

[13] “100,000 to March to Capital,” New York Amsterdam Star News, May 31, 1941; “March on Washington,” Michigan Chronicle, June 28, 1941.

[14] Jervis Anderson, A. Philip Randolph: A Biographical Portrait (1972; rpt. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), 248-49; Michigan Chronicle, June 28, 1941; Northwest Enterprise, March 21, 1941.

[15] Anderson, A. Philip Randolph, 259.

[16] “March on Washington is Postponed,” Minneapolis Spokesman, July 4, 1941; “Randolph Halts March on Washington,” Northwest Enterprise, July 11, 1941.

[17] Eric Arnesen, Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad Workers and the Struggle for Equality (Harvard University Press, 2001), 181-202.

[18] A. Philip Randolph, “We Need a New FEPC,” The New Leader, July 9, 1951, 12-13.

[19] Baltimore Afro-American, October 24, 1942; October 23, 1943; Michigan Chronicle, December 9, 1944.

[20] Black Worker (December 1961): 4-5.