Headline News | News

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2020: New York Union Local Gives ‘Dignity and Respect’ to Rev. King and The 1968 Memphis Sanitation Strike

Attributed by Jared McCallister

Published in New York Daily News

Separated by more than 900 miles in 1968, striking New York City sanitation workers were brought closer to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.-supported black sanitation workers strike in Memphis — through both coincidence and concern for their Southern colleagues.

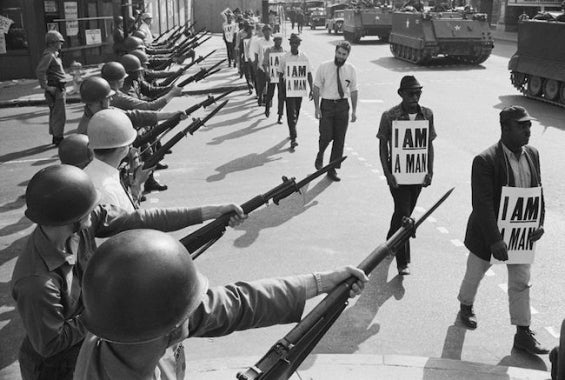

While the New York workers had wage concerns and other issues during their 1968 strike, their black counterparts in Memphis were enduring truly hellish and deadly working conditions and systemic racism daily.

And some New York sanitation union members even joined King and others by marching in Memphis for the beleaguered black sanitation workers.

What the Memphis workers were seeking by striking in 1963 was coincidentally reflected in the title of the 2009 Kevin Rice book about New York City’s Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, Teamsters, Local 831 called “Dignity and Respect.”

Nearly 40 years after the 1968 strikes, a connection of concern was again evident when New York sanitation union leaders pushed to recognize the Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday as a paid holiday for its workers.

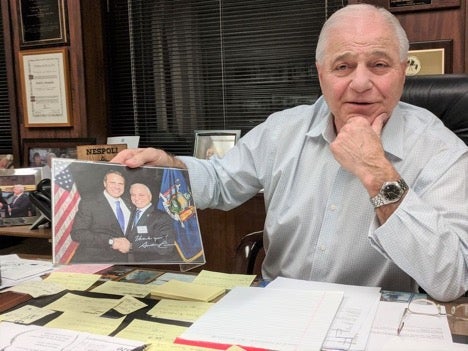

“I’m the only union that received this holiday without giving up a holiday,” said Harry Nespoli, president of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, Teamsters Local 831, proudly looking back on the achievement after negotiations with the city.

“I’m the only union that received this holiday without giving up a holiday,” said Harry Nespoli, president of the Uniformed Sanitationmen’s Association, Teamsters Local 831, proudly looking back on the achievement after negotiations with the city.

In 2008, the sanitation union members were the only uniformed city workers to get Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day off as a paid holiday without giving up another paid holiday to get it.

Nespoli – who starts his typical day in the wee hours of the morning, just like the thousands of workers he represents – championed the MLK paid holiday effort for sanitation workers.

His membership, nicknamed “New York’s Strongest,” works year-round to make all of New York City “new” every day by collecting tons of garbage and recyclables.

Every work day, Nespoli is at his desk in the union local’s lower Manhattan offices, talking on the phone and holding meetings, while always prepared to travel to meet with his members in the streets.

He is now also chairman of the Municipal labor Committee, which represents 100 municipal unions; vice president of International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Joint Council 16 in New York City and a Central Labor Committee vice president.

In 2007, with the support of local’s membership, he sought to add Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday to the union’s list of paid days off due to respect for the late civil rights leader’s efforts in general – and specifically for King’s support for the historic 1968 Memphis strike by black sanitation workers.

King’s show of support for the Memphis strikers sadly ended on April 4, 1968, when he was shot death at the city’s Lorraine Motel by an assassin.

At first glance, it seems possible that the black workers in the 1968 Memphis strike were inspired by the highly publicized work-stopping labor action in New York a week earlier, considering the large volume of news broadcasted from the media capital of the world.

But Nespoli – a man of conviction and commitment with a proven record of going the extra mile for his members – wasn’t going to assume connections between the two labor actions.

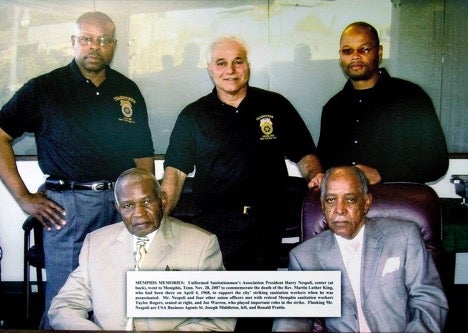

“I decided to take two of my sanitation business agents with me to Memphis, Tenn. I wanted to know more,” he said.

During sit-down with veterans of Memphis strike, Nespoli asked whether the New York strike inspired the black workers to hit the picket line in 1968. Their answer was: “No.”

“Did that strike up there have any effect on you? Nepoli asked at the Memphis strike veterans. “They told me no – it had no bearing at all,” said one former Memphis sanitation worker, revealing the hellish work conditions that did spark the strike.

“First of all, they didn’t have uniforms. They had regular clothes, and they had to go in the back of the houses in Memphis, Tenn., take the garbage cans from the back of the houses,” Nespoli said, recalling what Memphis workers shared. “There were sanitation workers that were going to the back of the houses, and people were shooting at them.”

Also, the 1968, black Memphis workers were not issued gloves or provided a place to shower after working with refuse all day.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me!’ They said, ‘No! This is how our job was down here.’”

Nespoli was shocked by the next revelation: the primary reason for the 1968 Southern strike was the deaths of two black sanitation workers who were crushed to death in a garbage compacter.

The incident was described in “Why We Need the ‘I AM 2018’ Moment of Silence: Remembering Echol Cole and Robert Walker,” writer Michael Honey’s 2018 tribute to the two workers killed, which was posted on the AFL-CIO.org website.

“As crew chief, Willie Crain drove the loaded garbage packer along Colonial Street, he heard the hydraulic ram go into action, apparently set off by an electrical malfunction,” read the article. “He pulled the truck over to the curb immediately, but the ram was already jamming Cole and Walker back into the compactor. The men were crushed like so much garbage.”

“That’s when they [the Memphis sanitation workers] said, ‘Enough is enough,’ and that’s when they went on strike,” said Nespoli. After returning from Memphis, Nespoli said, he responded to some New York sanitation workers complaining about their working conditions, saying, “I’m not saying you don’t work hard; I’m just saying there are jobs out there a lot tougher than what we have,” he said, thinking about the racial strife and the dangerous working conditions workers in Memphis faced.

Nespoli said he discovered that some New York sanitation workers “actually went down to Memphis, Tenn., and marched with Dr. King,” revealing another N.Y.C.-Memphis connection.

“I have to thank Mayor Bloomberg for recognizing the fact that it was necessary that this workforce have this holiday,” Nespoli said, adding that he “had to give up some money” to the city to gain the additional holiday, but union members felt it was worth it.

“Well, the mayor sat down [with us], and it just shows labor and management working together ¨ and we got it done,” Nespoli added.

“And that’s how we got it [the MLK Jr. Day holiday]. I didn’t get it for nothing. But people – representing the various segments of Local 831 such as the Irish, the Italians, Germans, the Polish, Hispanics and the Asians – came up to me and said, ‘That’s very good,’ referring to the union’s successful recognition of the MLK holiday.