The Minneapolis Strike

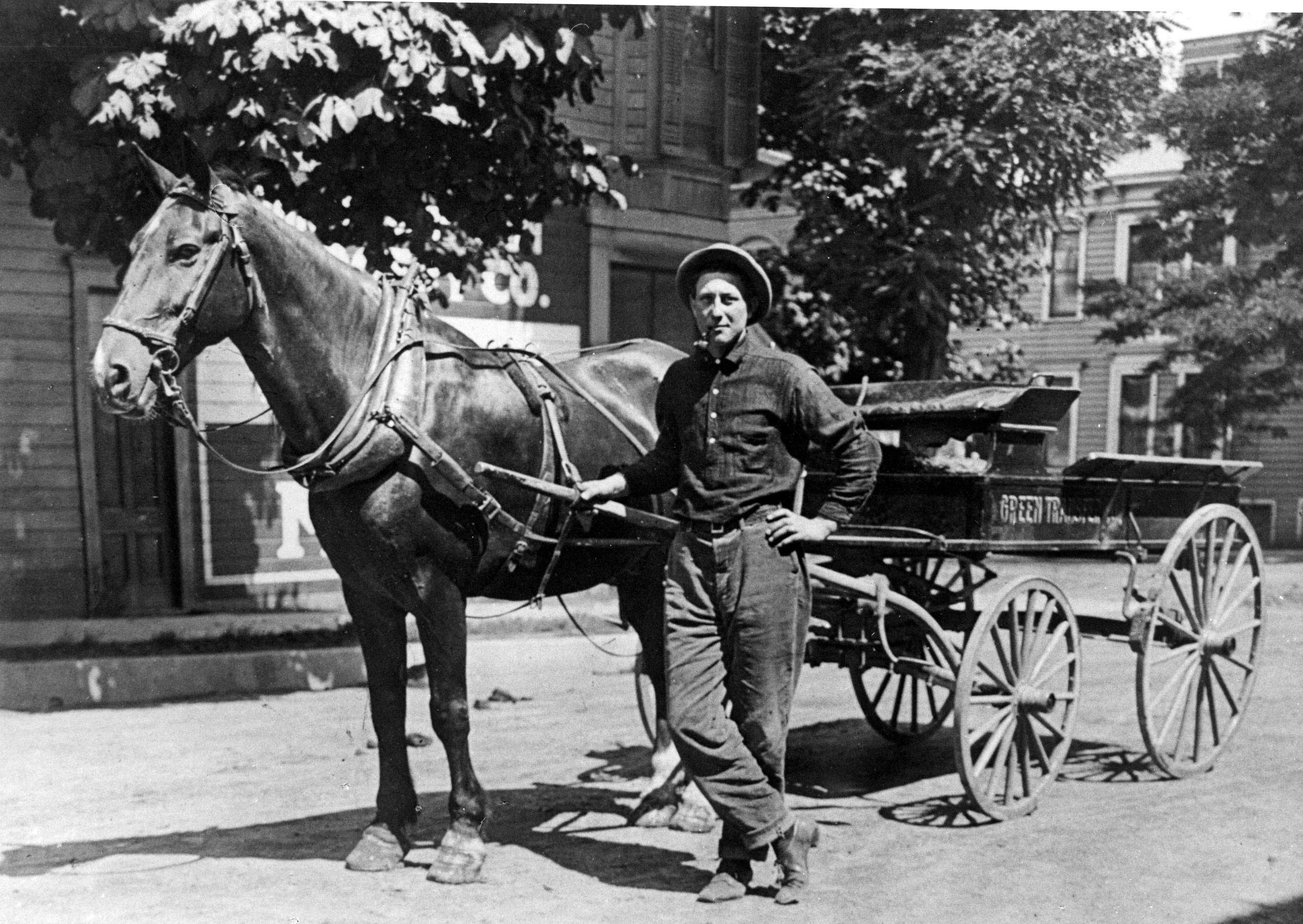

In 1934 Minneapolis was one of the major hauling centers of the United States, and the major distribution center in the Upper Midwest. Thousands of truck drivers were employed in the city’s trucking industry, but many were unorganized.

A small group of organized drivers in the city made up General Drivers Local 574 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. Local 574 had been trying for several years, with little success, to organize drivers in Minneapolis. They didn’t care what industry the drivers were from, they wanted to create one large industrial organization for all drivers.

A Hostile Environment

Union recognition for workers was difficult to obtain in Minneapolis. Since the turn of the century, an employers’ organization known as the Citizens Alliance had been the major force active during labor disputes in the city. The group consisted of a council of prominent local property owners and various right-wing elements active in local politics. The Alliance took a strongly anti-union line, and was often not averse to using violence to break up strikes.

But Local 574 finally got a break. In February of 1934, the local won a difficult strike at a coal yard and the victory prompted thousands of workers to join the union en masse over the next few months. This gave Local 574 an unprecedented boost, both in terms of membership numbers and credibility among drivers and warehouse workers. By May, the number of organized drivers and warehouse workers in Minneapolis had grown to 5,000.

But many companies in the city refused to recognize the union. The only recourse left to the workers was to call a general drivers’ strike.

Strike!

The strike began on May 16. The workers demanded recognition of the union, wage increases, shorter working hours and the right of the union to represent “inside workers,” workers employed in distribution centers but who were not drivers, such as warehouse and loading bay workers.

The strike brought all trucking inside the city to a standstill. It also used some techniques that were not normally used in labor actions.

Flying pickets were established and deployed from the union headquarters. They patrolled the streets in a vast fleet of cars and trucks to ensure that no scab trucks were on the move. They displayed a special union sign so as to prevent confusion.

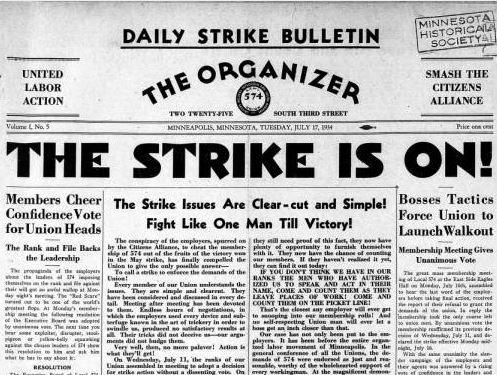

A committee of 100 strikers, which had broad representation from workers of most hauling companies in the city, was established to direct day-to-day issues and coordinate relief to strikers’ families. The committee established a daily newspaper, The Organiser, which reported information and news about the strike to members and the community at large.

A Women’s Auxiliary group consisting of female supporters and the wives of strikers was set up to conduct solidarity work from the union headquarters, such as organize daily demonstrations at city hall, beef up picket lines, run a food commissary and help operate a small hospital for strikers injured on the picket lines and their families. Some of the women even took part in street fighting when workers clashed with police.

The strikers committee also established an important link between the striking workers and organizations of the unemployed, who made up a third of Minneapolis’ working population at the time.

The support of the jobless towards the strike undermined the employer’s ability to find scab drivers.

Violence Erupts

The first major instance of violence was on May 19 when police attacked a group of strikers who were attempting to stop scabs unloading a truck in the city’s market area.

The market area became a central location for strike action and violence. Police attacks occurred again on May 21 and 22 when officers and members of the Citizens Alliance advanced on a group of 20,000 workers and supporters trying to stop the opening of the market area.

By this time, many other workers in Minneapolis had followed the Teamsters on strike in solidarity. About 35,000 building workers had walked out in protest of the police violence and many more struck for union recognition.

On May 25, employers in the city accepted many of the striker’s demands and worked through other issues with the help of mediators appointed by the governor.

The strikers returned to work, but in a matter of weeks it became apparent that the employers were not abiding by the terms of the agreement. Many union members were fired. Between May and July workers filed more than 700 cases of discrimination. The companies also refused to recognize their agreement to let the union organize inside workers.

The workers again took up the strike on July 17. Three days later, the most violent episode of the strike took place. A large group of unarmed workers were fired on by more than 100 police officers. They had been were lured to a street corner by deputies in a scab truck. The incident became known as “Bloody Friday.”

A public commission set up after the strike later testified that “Police took direct aim at the pickets and fired to kill. Physical safety of the police was at no time endangered. No weapons were in possession of the pickets.”

Two picketers, John Belor and Henry Ness, were killed and the hail of bullets. More than 65 other workers were injured. Many were shot in the back.

The police violence left the working class of Minneapolis stunned, and offers of support and donations flooded in from other unions.

Workers took part in strikes to protest the shootings, including a one-day strike of all of the city’s transport workers.

The Minneapolis Labour Review reported that a crowd of 100,000 people attended Henry Ness’ funeral.

Gov. Floyd B. Olson immediately declared martial law in Minneapolis, deploying 4,000 National Guardsmen at his disposal.

Picketing was banned and scab driven trucks—issued military permits—began to move again.

The union, seeing this as an attempt to break the strike, demanded that all permits be revoked and in defiance of the martial law, the workers vowed again to return to the picket lines on August 1.

On the night of July 31, the union headquarters was surrounded and raided by National Guard troops, who arrested many of the strike leaders.

But rather than hide, the union rank and file called a mass rally demanding the release of the arrested union leaders. Nearly 40,000 people marched on the stockade. The leaders were released and the captured union headquarters was surrendered.

Strike Ended

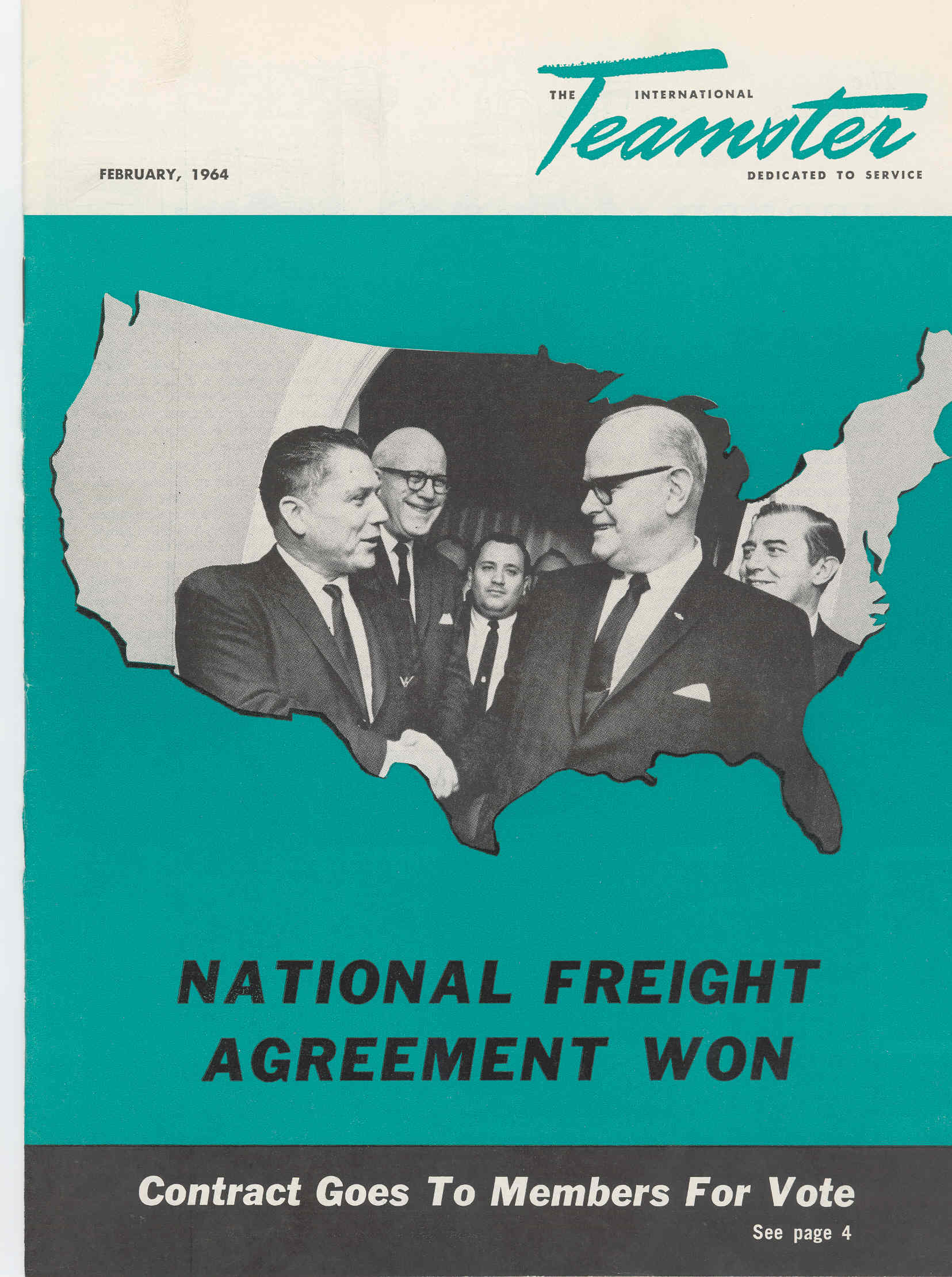

The strike finally ended on August 21. Through mediation, the employers and Citizens Alliance accepted the union’s major demands. Elections were held in workplaces and many more workers joined the union. Many workers also later won major pay increases through arbitration.

The Citizens Alliance had been broken, and with it the backbone of resistance towards union organization in Minneapolis. Workers in many other industries began to organize themselves and the city maintained a strong union presence throughout the 1930s.

The strike was instrumental in building a strong union tradition in Minneapolis and across the Midwest, with a writer of the Minneapolis Labour Review later noting that, “The winning of this strike marks the greatest victory in the annals of the local trade union movement … it has changed Minneapolis from being known as a scab’s paradise to being a city of hope for those who toil.”

The Minneapolis strike of 1934 is widely seen as a pivotal moment for the Teamsters and for the labor movement. Membership in the union grew as barriers against “non-craft” workers came down. The union also grew in stature, proving to be a powerful force in the labor movement. The outcome of the strike also led to the enactment of legislation acknowledging the rights of workers to organize and bargain, including the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act.